Since 1990, the real value added per construction labor hour has dropped by 23%. One fundamental reason is the opacity and fragmentation of construction workflows and activities — making sharing of information (aka communication) difficult.

‘Remember that Time is Money.’

— Benjamin Franklin, Advice to a Young Tradesman, 1748

The best way to achieve integration and transparency is letting information flow. However, in construction, the people working on the same project — from architect to crew — are in different places most of the time. As MIT professor Thomas J. Allen has proven in the 1970s: communication is highly correlated with physical proximity. It drops as a power law curve — after more than 10m distance, it ceases to happen. That’s why we remain bullish in solving the communications riddle in construction.

1/ On mid-to-large construction sites in the US, Foremen spend 3–5 hours of their day on communication.

2/ On similar sites Project Managers and Supervisors spend 7–9 hours of their day on communication. These numbers were fairly robust day by day in our field research, i.e. they didn’t vary a lot by site or by day.

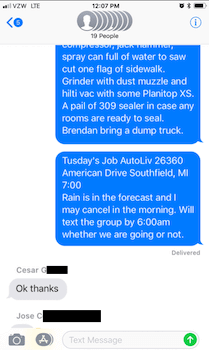

3/ And: Supervisor communication is still extremely non-digitally integrated. Want evidence?

4/ We identified 4 types of site communication. Informing, Scheduling/Purchasing, Resolving and Reviewing.

5/ Informing and Scheduling together make up 50+% of a Supervisor’s daily communication. Informing and Scheduling/Purchasing communication are transactional + contain repeated information.

6/ Ergo: Informing and Scheduling communication is well automateable.

7/ And: We have seen a variety of tech companies from Asia-Pacific, North America and Europe attack the communication opportunity:

8/ But: We have yet to see a solution that has an intense product-problem fit and well-working network effects and virality. Many construction communication solutions we get to see as part of our work in Foundamental have the issue that the Supervisor doesn’t get instant value. We believe that any construction communication solution needs to provide an instant benefit to the Supervisor. In some ways the issue is similar to why enterprise knowledge management has historically been hard to solve: the ones who have knowledge (senior experts, leaders) are usually not the ones instantly benefiting from filling the system nor do they have the time to fill the system. In construction projects, execution revolves around the Supervisor. Any solution that does not provide the supervisor instant value in his/her busy day with extremely low barriers for usage is — in our experience — unlikely to achieve 1000x growth on construction sites.

9/ The good news: One thing I learnt by spending my own research time in the construction trenches is that construction teams are a community and proud for mastering their tools. Any solution that does provide instant value at low usage barriers has a good chance to pull in the Supervisor’s network. Again, this is something that a few tech companies have stumbled upon, but they haven’t cracked the code for virality.

10/ Founder opportunities:

As always, credits go to the data wizards in our Foundamental Insights group.

Sources:

Within Foundamental we saw early that deep insights into construction workflows are critical for founders and co-investors. Hence, we decided to do something unusual for a VC: invest in our own on-site research. We partnered with a few like-minded individuals, and today spend 16-18 weeks per year on construction sites, in plants, and in trucks.

‘The success of a production depends on the attention paid to detail.’

— David Selznick

This year our interest in the logistics of building materials grew larger the more we looked into it. With Foundamental Fund 1 we made several investments in this space in Asia and North America — and are just getting started. That’s how much we love this space. So: this year we doubled-down on our field research around drivers for ready-mix concrete in India, USA, and European markets.

1/ Mixer drivers matter. A lot. The US ready-mix industry employs 75’000 drivers across ca. 5’600 plants. Drivers make up 56% of the entire US ready-mix workforce.

2/ And: The average age of a mixer driver is 46 years. The average tenure in the job was 10 years in 2017. These numbers suggest a highly experienced workforce.

3/ For good reason: Mixer drivers might be called „drivers“, but really they are „operators“. A ready-mix plant only stores and combines the ingredients — the actual mixing and initiation of the chemical reaction happens in the truck. The truck is part of the production line. The truck extends the plant on wheels. As a result, mixer drivers have to be able to assess the current condition of the concrete in the drum, in order to understand if eg. water can or should be added — or must not. They also operate the flow from the drum in conjunction with the pump. This matters because on larger sites the flow of a concrete pour is carefully spaced — usually in tight 15 minute windows — and must not be interrupted, or else cold joints might occur and the compressive strength of the entire concrete job is at risk. An inexperienced driver significantly increases the risk of job interruption, and with it the risk of financial damages for the ready-mixed producer.

4/ The problem is: the industry is short of mixer drivers. 48% of ready-mix plants reported lost business due to shortage of drivers in 2018. This number is up from 36% in 2017.

5/ And: driver retention is increasingly becoming an issue. 29% of drivers switched their employer in 2017 (up from 25% in 2016). This means: the average tenure of switching drivers was only 3.4 years in 2017. 66% of those switches were voluntary and initiated by the drivers.

6/ 58% of the drivers who quit stated that a better financial offer was a key reason for switching employers. 42% stated that improved work scheduling was a key reason for their switching.

7/ As a result: The ready-mix industry scrambles to replace drivers. The overall average tenure in the job dropped to 9 years in 2018, from 10 years in 2017. This number means 10% of the combined operational experience was lost in one year from 2017 to 2018. This is confirmed by another stat: 69% of ready-mix producers state that lack of ready-mix-specific experience is the major challenge in hiring drivers.

8/ Ergo: like all construction, the ready-mix industry has a workforce issue. When I first heard of mixer drivers two years ago my initial reaction was: “ok so let’s bring over drivers with a commercial drivers license (also called CDL) from the long haul industry“. Little did I know how much operational responsibility lies on the shoulders of mixer drivers. Their ability to judge the concrete condition and operate seamlessly is essential to an uninterrupted concrete job. I learnt: a simple hiring of drivers from other industries is not easily beneficial without years of training on the concrete itself.

9/ At Foundamental we are strong believers in automation of tasks on site as well as off-site to address the workforce resourcing issue in construction. From automation of drywalling over bricklaying to progress monitoring, we back transformative tech leaders who automate such tasks to a high degree. One such company in our portfolio is SafeAI, whose founders built a truly transformative solution to retrofit yellow machines for full autonomy on sites and in mines. However, the problem in ready-mix trucks is: those trucks drive 95% of their way in uncontrolled environments like urban streets and urban highways. A level 4/5 autonomy of those trucks remains unrealistic in the near term. As a result, we are strong believers that ready-mix trucks will still operate with drivers for years to come. But …

10/ … there are founder opportunities for augmentation instead of automation. Augmentation can reduce the need for operational ready-mix know-how and hence allow hiring more drivers without previous experience. We would like to see more founders/companies who attack in the following ways:

As always, credits go to the data wizards in our Foundamental Insights group.

Sources:

In Foundamental we look at more than 70 deals of early-stage tech companies in the construction sector per month across Asia, North America and Europe. One of the most frequent stats on founders’ slides we get to see is how much damage errors and rework are causing. These errors create a ton of claims and disputes in construction.

‘The degree of efficiency in an industry can be judged by checking its disputes.’

— Feodor Dostoyevsky, paraphrased

I recently realized that disputes are an interesting symptom of inefficiency in an industry. There are some industries that most people would call well-professionalized — for example automotive or aerospace — and where errors and disputes are under control.

After 2 years investing in tech companies in this space I can say: Construction is not one of those industries.

1/ The average dispute value on construction projects is around 8% of the project’s value. The average dispute then settles for around 2% of the value.

2/ And: for projects where the winning bid is 20+% lower than other bids, 70% of those projects have disputes.

3/ And: In North America, the main cause of dispute in 2018 was ‘errors or omissions in the contract document‘.

4/ But: Projects where the general contractor has a subjectively high expectation of future work with the same client, the rate of dispute drops to below 10%.

5/ Ergo: Contractors win contracts by underbidding. And: they claim 4x more than they settle for. When they are confident they win the next bid, they stop underbidding and stop claiming.

6/ Ergo: Incentives matter. A lot. Negotiation doesn’t stop with the contract — it carries on. The first incentive is winning the first bid. And then contractors want to win the next bid, ideally at a larger volume and better margin. Hardly a surprise for anyone who understands behavioral economics. But: at this scale incentives are out of control in construction.

7/ And: Transparency and objectivity matter. Getting away with a too low bid might not have been invented by the construction industry (defense industry, anyone?) but the EPC players might have perfected it. Opacity and un-objectivity result when speed or quality either (1) are subjective — which is fundamentally NOT the case in construction — or (2) are objective but cannot be measured objectively or (3) conditions or requirements change versus the initial agreement. What we see is this:

8/ Ergo: Disputes happen because contractors have incentives to win projects, and because they get away with under-bidding or under-performing as under-performance can be easily attributed to changing conditions rather than execution. With increasing resolution of measuring project execution, transparency and objectivity increase dramatically. In turn, they improve an owners/developers ability to judge speed and quality within a project and across projects.

9/ Question mark we haven’t figured out yet: In 2018, the average dispute value was $57 million in Middle East markets, with an average time to settlement of 20 months. In North America, $16 million (= 28%) and 15 months. Possibly a result of different project values, but maybe other contributing factors such as code, competition and business practices as well?

10/ Founder opportunities: We would like to see more founders/companies systematically addressing the following angles:

As always, credits go to the data wizards in our Foundamental Insights group.

Sources: